HandBound’s 18thC. Glossary of Clothing:

D-J

Eighteenth Century Terms of Fashion:

A Massive work in progress – please bear with us!

This glossary is based on an amalgamation between the historians: Iris Brooke, C and P Cunnington (and also Beard), Madeleine Ginsburg, Norah Waugh, James Laver, R.Wilcox, Liza Picard, Maureen Waller, Nancy Bradfield and of course, the wonderful Janet Arnold. It also uses Historical sources such as the Social Researchers Diderot and Garsault.

This glossary only covers British Fashions. The following information might not be relevant to outside of the UK: French and American and Continental Fashion might differ drastically.

DISHABILLE: 1713 onwards apparantly. This has got to be one of our favourite words, and it’s less of a garment and more of a look. The Cunnington’s quote from ‘The Guardian – 1713’. “We have a kind of sketch of dress if I may so call it, among us, which as the invention was foreign is call’d a dishabille. Every-thing is thrown on with a loose careless air.’…. We had to put it in – it’s such an interesting ‘style’.

DOWNY CALVES: We’re so totally fascinated with this idea that false calves could be ‘woven into the appropriate part of the stockings’ that we had to try and add this in. The Cunnington’s state that this was patented in 1788. Isn’t this amazing, who’d’ve thought men’s calves needed that much attention.

DRESSING GOWN: Men and Women both wore this item – for the men it’s described as a ‘loose sleeved wrap reaching the ground’ and frequently made of richly patterned silks. The Female version though – suggested to be only late 18th c onwards, was apparantly generally plain and made from a white cotton or wool and was very voluminous. This appears to be a term not used during the 18th century – the term ‘nightgown’ was used for both sexes – and also ‘banyan’ for the men’s version. The term ‘nightgown’ though is not to be confused with the term ‘nightgown’, lol, or ‘night-gown’ which also refers to a specific type of gown – nowadays known as a Robe a l’Anglais.

ECHELLES: Did you know that Echelle ribboned fronts were also worn in the 1600s! The Cunningtons state that they were worn from the end of the 17th century to the end of the 18th century. They say that it was the Stomacher that had the ribbons trimmed down the front. We’ve not got any examples of this yet, but lets concentrate on the 18th c love for it. (to be continued…)

FROCK and FROCK COATS: (Male and Female) – It’s quite interesting reading the history of these classic and well used kind of words. Today A Frock Coat is still a recognisable tailoring term, albeit an archaic one (it’s a style of formal jacket) and the word ‘frock’ can still be used to refer to a ladies or young girls dress – why? Why two completely different items of clothing and for the two completely different sexes? Well it appears to be in one complete beginning. In their ‘Dictionary of English Costume 900-1900’ the Cunnington’s state that the term ‘Frock’ was ‘FIRST used for a monastic habit’ – which kind of makes sense – a form of robe (hence the link with dress) and a male garment (hence the link with male clothing!). The Cunnington’s go on to say that from that time on it could also be used for a ‘loose, sleeved outer garment’ worn by workmen. In the 16th Century it was the term for a ‘loose jerkin or jacket’ but it’s the 18th century that we’re really interested in and the Cunnington’s State that ‘From c.1730’ it denoted ‘An Undress coat (except for the French Frock) following the changing styles of the body coat’ – they then specify that it was ‘always with a turn-down collar’. It seems that it was just called a ‘Frock’ and not a Frock coat at this part of the century. Buck agrees, describing the frock as: ‘in the first half of the century (the frock) was a coat for easier informal wear, distinguished by it’s turn-down collar and unstiffened pleats. (Italics ours) It was usually of plain cloth; if there was trimming it was limited to a binding of gold of silver lace.” She also goes on to say that by the mid 40’s the frock had become to be more dressed with ornamentation and therefore worn for less informal occasions and by 1761 it was being worn by Lord Huntingdon at a ball at Norfolk House but what’s interesting here is that it still wasn’t a totally accepted form of clothing for a formal event: he had to come ready with an excuse and thus pretended he had just come in from ‘the country’ – ie, he’d just got off his horse from visiting a more hunting related place. It was a slow journey from sports wear to fashion!

At the end of the 18th century the term ‘Frock’ had become a little posher and the added word of ‘Coat’ had been put onto the end. It seems that this is when it moved up into the more acceptable ‘Dress’ section of the wardrobe. The Cunnington’s purposefully specify that the term ‘Frock Coat’ wasn’t used until this time and by then it had developed a fashionable deep Turn-Down collar and Tails. The image we’ve used to show this is not ideal – we will try and replace it with a better one (it’s on our job list!) but you can just about see the details here – the great and deep fall down collar and the narrowing skirts into tails.

it moved up into the more acceptable ‘Dress’ section of the wardrobe. The Cunnington’s purposefully specify that the term ‘Frock Coat’ wasn’t used until this time and by then it had developed a fashionable deep Turn-Down collar and Tails. The image we’ve used to show this is not ideal – we will try and replace it with a better one (it’s on our job list!) but you can just about see the details here – the great and deep fall down collar and the narrowing skirts into tails.

The term ‘Frock Coat’ then moved on into the 19th century where it became more shaped at the waist and a full skirt but with the vent and side pleats. That more shaped waist then became a waist seam, the coat developing on to have Lapels and suddenly the term split into two where it became the ‘Morning Frock Coat’ and the ‘Dress Frock Coat’ (now into the 1870’s!).

– Jemmy Frock: Male: Is a type of Frock coat –

For the Female aspect of this word, the Cunnington’s (again) say that it was a word used to describe an ‘Informal Gown’ in the 16th and 17th Centuries. ‘From the 17th c. on’, they say it was also to applied to children’s dresses which is pretty much where it remains today. It is possible to say to a friend ‘nice frock!’ and therefore the acceptable use of this term for a ladies dress is real, but it’s kind of said in a quirky, antiquarian manner – ie a bit more fun than just saying ‘nice dress’. We’ve yet to research if the term ‘Frock’ moves off from children’s wear through the 19th C, and perhaps it gained strength in the 1940s and 50s with women’s wear – we’ll update this page once we’ve done a bit more reading, but for 18th C Britain – it was a nice word for childrens wear.

FURBELOW: Female. This was the word for the trim that adorns many eighteenth century gowns along the Centre front edges, sleeves and often on the stomacher. It is made up of the self fabric of the dress and is either pleated or gathered or puffed into a trim that can be placed straight on the garment or in swirls or waves. The other exception was for the furbelow’s to be made of lace. The Cunnington’s state that Furbelows were out of fashion between the 1715 and 1750. They also state that they ‘were never worn with closed gowns’.

edges, sleeves and often on the stomacher. It is made up of the self fabric of the dress and is either pleated or gathered or puffed into a trim that can be placed straight on the garment or in swirls or waves. The other exception was for the furbelow’s to be made of lace. The Cunnington’s state that Furbelows were out of fashion between the 1715 and 1750. They also state that they ‘were never worn with closed gowns’.

GOWN: Essentially Female. This item of clothing could also be called a ‘Robe’ or a ‘Dress’, and can also be broken down into the various styles it comes in, i.e ‘Polonaise’ or ‘Sack’. It does seem that the term ‘Gown’ is what most ladies were using in their letters here in 18th C. England, to describe their dresses. We’ve even got a theory that when they use the word ‘gown’ they are actually referring to the Robe a l’Anglais specifically as they then can use the terms ‘sack’ for the Robe a la Francais and Mantua in the same letters. Tis just but a theory but one we’d like to research deeper. It could be viewed that the word ‘robe’ is the french term and the word ‘gown; is the english, but this isn’t necessarily true either. The word ‘robe’ does indeed stem from Old French but it’s in use in England in Middle English (11oo to 1500 ish) so was well settled in our language by the 18th century but for whatever reason, as far as we’re aware, it only seems to be used for high formal garments and priestly garments. Writing this makes us want to go back over all the few letters we’ve read so far, just to double check no-one’s indeed using the word Robe, but it is how we perceive things at the moment.

The word ‘gown’ is celtic based from ‘gwn/gunn/gun/goon’ and appears in Middle English as ‘goune’. Interesting isn’t it!

So, with the history lesson over, here following is the Breakdown of the various styles of ‘Gowns’ that appear in the 18th Century:

– Polonaise:

HATS:

– Balloon hat or Parachute hat: Mainly during the tall hairstyles of the 1780’s, this hat had a ‘large ballooned crown and wide brim’ (Cunningtons). Made of light-ish fabrics and of a wire frame. The Cunningtons states that they were worn as a compliment to Lunards and his balloon.

– Bergere Hat: (F) Basically another name for the Milkmaid Hat. A low crowned straw hat with large brim, usually tied with ribbons to under the chin or round the back of the neck or held into place by hat pins. Cunnington gives the dates 1730’s – 1800’s for the main period when this item of wear was fashionable.

– Dettingen Cock: (M) – According to the Cunnington’s this is a form of Tricorne – being ‘high equal cocks, front and back.’

HEAD DRESS TYPES: These don’t really come under the terms of caps or bonnets as they aren’t so much something to cover the head as to display in the hair.

– Cabriole or Capriole Head dress: 1755-57. This was a carriage shaped head dress. I don’t think this is to be confused with the high hair-dressing of the 1770’s where whole ships were fashioned in. Not really sure what this would look like but Cunnington and Beard mention is and thought it was an interesting point. They use a quote from The Connoisseur from 1756.

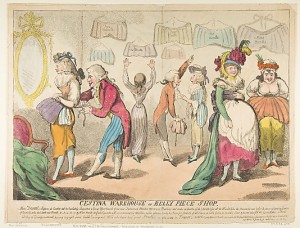

HOOPS:

First off – just to clear up any confusion, I’ll remind the reader that the term ‘coat’ could be the Eighteenth century shortened word for ‘Petticoat’. So the Bell Hoop or the Cupola Coat was the petticoat that sprung into fashion in 1709. (Brooke). This was the re-entrance of a stiffened underskirt and in this century was fashioned with cane or whalebone.

Contemporary sources from the time suggest that this ‘new device’ might have originated from some foreign court where the Farthingale had never quite gone out of fashion. It was either made from canvas or fashionable fabrics (Waugh)and shaped with either Rattan cane or Whalebone.

– Bell hoop or Cupola coat: The Bell Hoop is, as it’s name suggests, was a large bell shape and fully circular in it’s rotundity.

The French welcomed the English version of this hoop in replacement to their more uncomfortable version and called it the ‘Panier Anglais’. This is where the term Panniers comes from. In this image here by Crespi – you can see the orange Bell hoop hanging on a chair. It is an un-covered Hoop with links connecting the circles of cane/bone.

Again in 1714 (Brooke’37) another adaption arrived. The Fan Hoop – This new shape was flattened at the middle and back and created a more oval shape, rather than the massive circle of the Bell hoop. This did not completely replace the Bell Hoop but, according to Cunnington and Beard both were fashionable alongside each other for most of the Eighteenth Century. Cunnington and Beard suggest the dates 1710 – 1780’s for the Bell Hoop. But Iris Brooke seems to suggest the Bell Hoop dropped out of use by the 1750’s. She does not state this but you do not hear of it again, outside of these dates and images certainly seem to support this. On page 100 of her book ‘Dress and Undress’ she writes on hoops being discarded for a fashion: It was towards the end of the fifties that the really fashionable began to discard their hoops except for full dress. The hoops as worn until about ‘fifty five were unusually large and had developed into the panniers or side hoops that not only complicated movement and sitting down, but also made an amusing sight in a strong wind…”.

However, in the book ‘The Beautiful Mrs Graham’ on page 272, as late as 1792 Lady Cathcart writes to her sister from Whitehall: ‘The Duchess of York danced a great deal at the last ball, and very remarkably well, as if she had been much used to English Country Dances, which is more than I can say of her German lady Mlle. Von Verack who sailed down the Dance in a Bell Hoop and Arms extended in a most extraordinary manner.’ Obviously it was so odd that it was worth mentioning in a letter but it is an example of the Bell Hoop still being worn in 1792.

– Fan Hoop. This was name of the new hoop that came in during the year 1714. This particular hoop was wider at the hem than at the waist, hence the name ‘fan’ and was flattened in the middle. Like the Oblong hoop, these hoops, in size; could be incredibly wide at the hips or right down to a smallish support system for the skirt, but always retaining that fan like shape. For our example of this hoop we have used The Fanshaw dress found in the Museum of London’s Collection and dated 1750. this would be classed as Court wear so the progression up the fashion scale can been seen. For more info on this dress please see our page: ‘The Fanshaw dress’. The Cunnington’s suggests that this was most fashionable during the 40’s and 50’s but there are still many dresses and fashion plates right in to the 1780’s that have this silhouette and for high court wear it’s well known that Queen Charlotte insisted they be worn. So, we’re going to suggest that the following dates apply:

– 1714 – 1740’s fashionable in ‘Undress’ and ‘Dress’ gaining strength towards the 40’s – this is only according to the Historians though – it’s hard to find evidence of this in the paintings of the time.

– 1740’s- 50’s – fashionable in ‘Undress’ and now in to ‘Dress’ wear.

– 1760’s – 1818 – fashionable only in ‘dress’ but progressively more into ‘Court Dress’. There seems to be a slightly more complex hierarchy of dress than just plain old ‘Undress’ and ‘Dress’ – fashions varying for all sorts of occasions and levels of occasions but for now we’ve split it into 3 general forms: ‘Undress’, ‘Dress’ and ‘Court Dress’.

There is possibly another version of the Fan hoop, which was the Kidney Hoop (Waugh) which apparantly originated in France. It’s unclear as to whether or not she means that the Fan hoop is the Kidney hoop or that there was a steaming of the boning to make it have a kidney shape to it along the bottom hem.

– Oblong or Square Hoop/Coat: The main characteristic of this hoop is that it is pretty much a rectangle, so whether it comes out 3 foot from the hips or just a mere 8 inches, it’s shape still remains a box-like shape. Waugh ’54 suggests that this was mainly worn in England. This is also the 2nd most prevalent Hoop. Along with the Fan Hoop, these two hoops make up 99% of the images out of there of dresses photographed with hoops. (P.S. this is our wonderful non-scientific approach to statistics…)

It’s an interesting summary to know that most of the hoops in the museums date from c.1760 onward.

IRISH LINEN: (F or M) Irish Linen, during the 18th c, became an established type of linen, popular for it’s quality. Manufacturers from all over the country were specialising in some area of fabric/fashion, be it ribbons, kid gloves, linens or cottons. Buck goes into this topic beautifully and covers quite a lot of the moving about of specialising areas. The factories in Ireland certainly were excelling in Linens and were becoming famous for it. Printed Linens tended (and we only say ‘tended’) to be made into Day Dresses or what was known then as ‘Undress’, therefore Linen could often become a by-word for Undress.

IRISH POLONAISE: (F). Apparantly also known as an Italian, Turkish or French Polonaise and the way the Cunnington’s describe it in their Dictionary could be a normal Polonaise with a short petticoat. “1770-75” they describe it as a Day Gown with a ‘close fitting, low, square-cut bodice fastened close down the front and fitting behind…’

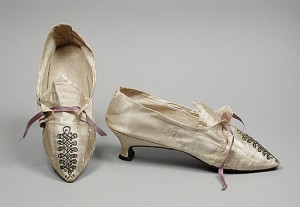

ITALIAN HEEL: (F) A shoe style which we’re pretty sure can still be referred to as an Italian Heel even today, and which we could describe as essentially what we’d call a ‘Kitten Heel’. From the Cunnington’s description and drawing it’s a short shaped Heel that sits a little in from the back. The Cunningtons also state that this heel comes into fashion from the 1770’s onwards.

JACKET: Do we really need to spell this item of clothing out, you may ask. So simple a term, yet words can change their meaning over time. The Cunningtons actually have quite an interesting insert for this. Are we allowed to quote the whole thing? Well we’ll pick the best bits:

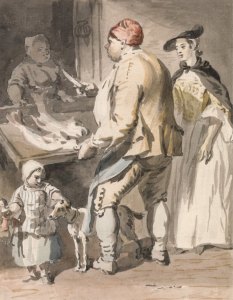

“Throughout the 18th C. the jacket was the main body garment ‘in use among the country people’ (1706, Phillips) and also worn by labourers, apprentices, seafarers, postillions and sportsmen; thus becoming a symbol of social inferiority; in the 18th c. the gentleman used it only when powdering.” (ie the Powdering Jacket).” Obviously they wore coats but it goes to show that there was a distinct difference between a coat and a jacket. We at HandBound Costumes evidently make this mistake all the time – coming from a tailoring back ground we’d much more readily apply the word ‘jacket’ than ‘coat’ to such a garment; the modern day progression of the word ‘Coat’ now describing an outdoor garment. The Cunnington’s have not included a picture in their Dictionary so it’s hard to know exactly what they were talking about for sure, but pull up a collection of images with working class men in them and you being to see a similarity. The Working man’s jackets tended to be shorter, more ill fitting and always lacked the fashionable cutting away of Gentlemens coats. They seems to have a more of a box-like cut to them and the CF edges were straight and functional. Perhaps it was these kind of features that clearly separated them to the 18th c. eye as ‘jackets’ rather than ‘coats’.